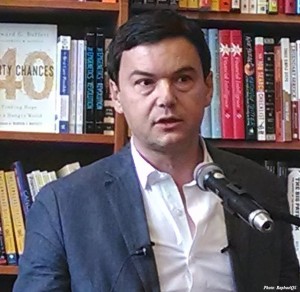

It was with some delight that I read the introduction of Thomas Piketty’s book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Right from the beginning, he announced that he would not be bound by “the childish passion for mathematics.” Rather, his approach would include the social sciences since “economics should never have sought to divorce itself from the other social sciences and can only advance in conjunction with them.” Piketty even threw in some passages from French and English literature to serve as bona fide proof of his break from economic orthodoxy.

It was with some delight that I read the introduction of Thomas Piketty’s book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Right from the beginning, he announced that he would not be bound by “the childish passion for mathematics.” Rather, his approach would include the social sciences since “economics should never have sought to divorce itself from the other social sciences and can only advance in conjunction with them.” Piketty even threw in some passages from French and English literature to serve as bona fide proof of his break from economic orthodoxy.

Of course, Piketty is right. As a social science, economics must consider factors outside the realm of numbers. Economics deals with the human activity of production, administration, and exchange of goods and services. Human actions, being fickle, are not predictable with mathematical precision. In addition, transactions often involve moral actions, and so to properly judge, order, and interpret these actions, the economist needs to work in conjunction with the social and normative sciences.

Is Technology Ruining Your Life? Take A Quick Quiz To Find Out By Clicking Here.

However, my delight soon turned to disappointment. After his emphatic declaration of war on modern economics, I was surprised by Piketty’s failure to abide by his own rules of engagement. We are immediately introduced to his mathematical formula of “r>g” (meaning, “rate of return is greater than growth”) from which he explains the inevitability of “excessive” inequality in almost classical fashion. There are literally dozens and dozens of supporting charts. The reader is immersed in numbers, figures and data.

on modern economics, I was surprised by Piketty’s failure to abide by his own rules of engagement. We are immediately introduced to his mathematical formula of “r>g” (meaning, “rate of return is greater than growth”) from which he explains the inevitability of “excessive” inequality in almost classical fashion. There are literally dozens and dozens of supporting charts. The reader is immersed in numbers, figures and data.

Granted, he may draw upon sources that may qualify as coming from the social sciences, but there are two things that are disconcerting about Piketty’s “social science” approach.

To read more, click here