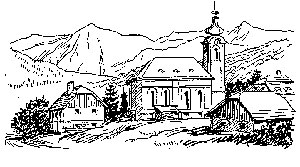

Far beyond the ocean, in a valley in the Austrian Alps, lies the age-old village of Oberndorf, looking now much as it did one, two, or three hundred years ago. In the center of the village, near a swift-flowing stream, stands a whitewashed church with a tall red-topped steeple. The low houses, their slanting roofs weighted down with stones, are scattered about the church like so many baby chicks around a red-combed white hen; and the church bell calls to them from the steeple in a quick, excited hen-like tone.

Far beyond the ocean, in a valley in the Austrian Alps, lies the age-old village of Oberndorf, looking now much as it did one, two, or three hundred years ago. In the center of the village, near a swift-flowing stream, stands a whitewashed church with a tall red-topped steeple. The low houses, their slanting roofs weighted down with stones, are scattered about the church like so many baby chicks around a red-combed white hen; and the church bell calls to them from the steeple in a quick, excited hen-like tone.

In the days of our story only peasants and a few artisans lived in Oberndorf, with an occasional trader coming in “from outside.” There were but two educated people in the village: Father Joseph Mohr, the twenty-six-year-old parish priest, and Franz Xaver Gruber, the organist and schoolteacher. Both being young and “from outside,” they soon became fast friends, and every Sunday they met to make music. As Gruber sang the bass parts to Father Mohr’s tenor and played the accompaniment on the guitar, the children gathered in the street before the rectory and nudged one another: “Listen, the priest and the teacher are singing again.” They enjoyed these informal weekly concerts.

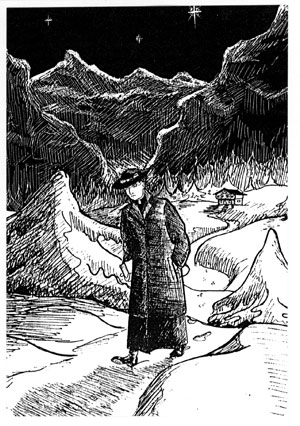

On the twenty-fourth of December, 1818, Father Mohr sat alone in his study, reading his Bible. The sun had set behind the western mountains, and the blanket of snow draping their peaks had turned a steely blue-gray above the black forest, except where the first stars cast their silvery gleams on them. All through the valley the children were filled with excitement, for it was Christmas Eve and they would be staying up to attend Midnight Mass.

The young priest, sitting at his oaken study table and working on his sermon for the midnight service, had no eyes for the festively lighted valley just then. He had read chapter after chapter and had come to the story of the shepherds in the fields to whom the angel announced: “Behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy, that shall be to all the people. For, this day, is born to you a Savior.”

Just as Father Mohr reached this well-known passage, someone knocked at his door. He rose and opened it. In came a peasant woman, wrapped in a coarse shawl. He knew that she lived on one of the highest alps in his parish. “Praised be Jesus Christ,” she greeted him. Then she went on to tell him of a child born earlier that day to a poor charcoal-maker’s wife. The parents had sent her to ask the priest to come and bless the infant, that it might live and prosper.

Father Mohr got up, put on his coat and mittens and overshoes, and followed the woman through the knee-deep snow of the spruce forest. The priest noticed neither the trails of animals in the fresh snow nor the brightly glistening stars, even as the one that had led the Wise Men to Bethlehem when they bore the world’s first Christmas gifts. Rather, he turned over in his mind the sermon he had to preach, for which he had nothing prepared.

What Does Saint Thomas Say About Immigration?

At last he and his guide came upon a ramshackle hut. A big, awkward man respectfully greeted the priest and invited him to enter. The hut was low, filled with wood smoke, and poorly lighted. But on the crude bed lay the young mother, smiling happily, and in her arms lay her baby, peacefully asleep. Father Mohr baptized the infant and gave them all his priestly blessing and a few kindly words, then excused himself and departed.

He felt strangely moved as he trudged alone back out into the snow. The smoky mountain shack, with its crude bed, did not resemble the manger in the City of David; yet, somehow, the last words he had read in his Bible suddenly seemed addressed to him, Joseph Mohr. It seemed that the Christmas miracle had just happened before his eyes. As he made his way carefully down the mountain, he felt the promise of peace and goodwill in the silence of the forest and in the brilliance of the stars.

Coming at last into the valley, he saw that the dark slopes were alight with the torches of the mountaineers on their way to church, and from all the villages, near and far, bells began to ring and echo from the mountain walls: “Jesus Lord, at Thy birth….”

To Father Mohr, a true Christmas miracle had come to pass. The young priest celebrated the Midnight Mass, preached his sermon, and returned home. But he found no sleep. He sat in his study and tried to put on paper what had happened to him. The words kept turning into verse, and when dawn broke, Father Mohr had written a poem.

What does Saint Thomas Aquinas say about Marriage?

Franz Gruber, the other musician in Oberndorf, was twenty-nine when he became a teacher at the village school. As he no longer had his spinet, he soon learned to play the guitar of his new friend, the priest, to the delight of the village children who gathered about to hear their priest and teacher singing.

The two had been friends for two years on that Christmas Eve when Father Mohr wrote his poem. Little did he know that this poem would one day become the world’s best-known Christmas song. He had, quite simply, put his own miracle on paper. Wanting to give the poem to his friend for Christmas, he took it to him early the next morning.

The teacher read it over, and then read it a second time. Greatly moved, he said: “Father, this is just the Christmas song we need. God be praised.”

“But without the right tune, the words will be pretty lonely,” objected Father Mohr.

Franz offered to compose some music and went right to work on it. Since the church organ was out of order and he had no preparations to make in church that morning, he could use the time for working on the song.

Father Mohr, meanwhile, celebrated the Christmas Day Masses. Afterwards, as he contemplated the wax figures in the nativity scene — the Christ Child in the manger, His virgin mother arched over Him, and Saint Joseph standing reverently and protectively at His side — it seemed as though he had never seen the Holy Family look so alive. Though the organ had been silent, he thought he had heard singing and chiming during the service, as of a heavenly choir.

Not much later, Franz came to him, an hour before the appointed time, with a broad smile on his face and a sheet of music in his hand. “Here it is,” he announced. “It was easy; your words sang themselves. Let’s play it.”

“But how?” asked the priest. “We have no organ.”

Gruber chuckled. He had thought of that and had arranged the notes for what was at hand — two voices and a guitar. “The dear Lord,” he said, “can hear us without an organ.”

And so, on Christmas Day of the year 1818, the village children once again gathered in the street. They had no inkling of the significance of the event they witnessed that day, least of all that it was the birthday of a song that would be sung everywhere that Christmas is celebrated. No, they heard only their parish priest and the teacher singing, as usual, to the accompaniment of the old guitar.

All is calm, all is bright.

Round yon, Virgin, mother and child;

Holy infant, so tender and mild,

Sleep in heavenly peace,

Sleep in heavenly peace.

Thus did “Silent Night” come into the world, destined not just for little Oberndorf, but for the whole of Christendom. The same Divine Providence that had undoubtedly brought it into being through the pen of a good priest and the musical talent of a village teacher, had deigned that “Silent Night” should become the world’s Christmas carol.

Here is how this came about.

One day a prominent organ maker of the region came to repair Oberndorf’s organ. He was Karl Mauracher, a venerable gentleman from a valley of the Zillertal in Austria. In a little while, he had the organ working as good as ever.

Franz Gruber settled in front of the keyboard. The church soon resounded with the sweet chords of the new Christmas melody, sounding far better on the organ than on the guitar. Father Mohr and Gruber promptly began singing together.

Mauracher listened in awe. When the last note died away he asked Gruber to play it again. Gruber happily obliged, and he and Father Mohr sang again.

“Where did you get that song?” Mauracher asked when it was finished. “I never heard it.” The priest and the teacher exchanged smiles but said nothing.

Mauracher had such a gifted memory for music that by just listening to the song twice he had learned both the melody and the words. So it was that he took it back with him to the Zillertal where the local children, always eager to learn a new tune, soon picked it up. Since no one in the Zillertal knew who the author of the song was, and because of its tranquil, penetrating, and heavenly melody, it soon became known there as the “Song from Heaven.”

Mauracher had such a gifted memory for music that by just listening to the song twice he had learned both the melody and the words. So it was that he took it back with him to the Zillertal where the local children, always eager to learn a new tune, soon picked it up. Since no one in the Zillertal knew who the author of the song was, and because of its tranquil, penetrating, and heavenly melody, it soon became known there as the “Song from Heaven.”

Among the songsters of the Zillertal there were four children who excelled in music because of their voices. These were the Strasser children. Caroline was the oldest, followed by Joseph, Andrew, and the very young Amalie. They loved the new song that Mauracher taught them and soon had arranged it for four parts. On the following Christmas they sang it to surprise their parents.

The Strasser family made fine chamois gloves. When the children were old enough to help their parents in selling the gloves, they sang while waiting for customers, and every time they sang “Silent Night,” no matter how long past Christmas, people always crowded around to listen and seldom left without purchasing some gloves.

As the children grew older, their parents sent them to the surrounding towns with baskets packed with their finest wares. One day they travelled all the way to Leipzig, in the Kingdom of Saxony, where the world’s greatest annual trade fair took place. There, having set up shop, they began to sing the many folk songs they knew, but the one they sang most, for it was their favorite, was the “Song from Heaven.” They saw that its charm worked even in that busy city, as people began to gather around.

One day, a well-dressed, elderly gentleman greeted them. He asked the children if they would be so good as to agree to sing their folk songs for an audience. The children, quite taken aback by the thought, replied that they had to be getting back home for Christmas.

The following year, as soon as they had set up their little booth, the same gentleman made his appearance, this time asking them to accept four tickets to an orchestral performance. He gave them the address and the date and left the children absolutely delighted with the idea of attending a real musical concert for the very first time in their lives.

And so it happened that on the appointed day the children found themselves seated in four of the best seats in a magnificent gilded performance hall. People of all social classes were there, from simple folk and merchants to the best nobility of Saxony. Then came an announcement: “Their Royal Majesties the King and Queen!” The Strasser children, awestruck with all of this, were further amazed at seeing that the conductor of the great orchestra assembled before them was none other than the elderly gentleman who had given them their tickets. He was the Director General of Music in the Kingdom of Saxony! To their yet greater surprise, he suddenly turned and announced that there were four young persons present who, although not singers by profession, had some of the best voices he had heard in years. Perhaps, he said, they could be persuaded to treat their Majesties to some of their beautiful Tyrolean tunes. The youngsters faces reddened and they froze in their seats! But then little Amalie had an idea: “Let us shut our eyes and pretend we are at home.”

And so they did. Their first song was “Silent Night.” With the first notes, all of their stage fright vanished. To their listeners it was as though the young voices were bringing the tranquility of a mountain winter night into the crowded hall.

When they finished there was a moment of reverent silence. Then the applause broke loose and went on and on. The director, smiling broadly, patted the Zillertalers and told them to sing some more. They sang all the songs they knew, and when they knew no more, they sang “Silent Night” again. The applause was immense. The audience was entirely charmed. The King and Queen then invited the children to their box, for they wished to meet these nightingales of the Zillertal. Trembling a bit, the children went to the Royal box. Here they were invited, by their Majesties themselves, to sing at the palace! Even though that meant spending Christmas away from home, they could not refuse the King and the Queen, and so they accepted.

This Christmas marked fourteen years to the day that the two friends in the mountain village had written “Silent Night,” and still no one knew who its author was. People knew only what Joseph Strasser had told the king of Saxony — that it was a Tyrolean song. To the Zillertalers it was still the “Song from Heaven.”

Thus, “Silent Night” spread throughout the German provinces by means of the Strasser children. As the years went by, the little song struck out a path of its own and one day appeared in the cathedral hymnal book of the King of Prussia. One Christmas season, as the King sat in church, he was struck by the beauty of a particular song the choir was singing. Looking at the song in the hymnal book in his hands, he read the name “Silent Night” and the phrase “Author and composer unknown.”

Frederick William of Prussia was a meticulous man who liked having everything properly arranged. He could not believe that his orderly Prussian hymnal could have such a deficiency as a song with “Author and composer unknown.” He immediately ordered that the choirmaster be called to his presence. The poor man could not answer His Majesty’s query about the origin of the song.

Inquiries were made all around, but no one knew who composed the heavenly melody nor how the song had been included in the King’s hymnal. Now, there was in the kingdom a man who had a reputation for knowing everything there is to know about every kind of music. This was the Royal Concert Master, Ludwig Erk. But not even Ludwig could not satisfy the King’s curiosity. He simply did not know — for the first time in his life. He had never heard anyone speak of the origin of the song.

And so it came about that the Royal Concert Master received a mission from the King himself: to explore Europe in search of the origin of the mysterious, heavenly tune “Silent Night.”

Erk began his search in the Berlin library, but found nothing. Then, scrutinizing the song itself, he concluded that it seemed Austrian. It could perhaps have been composed by Mozart or Haydn. Ludwig decided to go directly to Vienna. There he searched high and low. Finding nothing, he took to the road once more, visiting many Austrian towns and cities — all to no avail. The Royal Concert Master eventually found himself sitting at a modest country inn just before crossing the German border. It was a charming inn; the food was good, the innkeeper was very polite and, in one corner, a caged bullfinch warbled sweetly. But Ludwig Erk noticed little of this. He just sat there frowning, wondering how he would explain the failure of his mission to the King. Suddenly, however, he noted with a start that the bullfinch had started warbling “Silent Night”!

“Where did you get that bird?” Erk asked the innkeeper.

“A traveler left him,” replied the innkeeper. “The man said he bought the bird in Salzburg, at Saint Peter’s Abbey.”

Ludwig Erk made straight for the abbey, an imposing edifice founded a thousand years before and where he knew Michael Haydn had once stayed. The venerable Abbot himself received the royal envoy, surrounded by all his monks. Erk quickly explained his mission, but neither his humming nor playing of the tune nor the story of the bullfinch provided a clue. The monks did not go in for training songbirds, the Abbot explained. Indeed, such was forbidden.

Nevertheless, the monks were more than happy to show him into the room Haydn had occupied, which was kept just as he had left it. There, Erk spent a full week perusing all of Haydn’s books and writings. Although Haydn had written many beautiful songs, “Silent Night” was not to be found among them. The search for the origin of “Silent Night” seemed to have reached another dead end.

In this life, however, ends are frequently only beginnings in disguise. The choir inspector, Ambrosius Prennsteiner, knew that one of the mischievous boys in the school attached to the abbey could easily have trained a bullfinch to sing “Silent Night.” It just remained for Prennsteiner to do a little detective work.

[like url=https://www.facebook.com/ReturnToOrder.org]

While all his boys awaited him at the vestry, he secretly posted himself outside the window and, with a leaf before his lips, whistled “Silent Night” in the manner of a bullfinch. After but a few bars, he heard one of the boys inside yelling, “Hey, you, your bird has come back!”

Well, so far, so good, thought Prennsteiner, and he continued whistling. A moment later, he saw one of his nine-year-olds tiptoe around the corner to catch the winged singer, only to stop dumfounded at the sight of the inspector. “Well, well,” said Mr. Prennsteiner, “what’s your name?”

“Felix Gruber,” the boy replied in a small voice as he prepared to bend over. With a bit of further inquiry, the author of the “Song from Heaven” was finally discovered. Felix was the son of none other than Franz Xaver Gruber.

The choir inspector paid the composer a visit. Gruber was immensely surprised at the travels of his little song. He told Prennsteiner all about the origins of “Silent Night” from the inspiration of Father Mohr, who had died by then, and he corrected a few alterations that the song had suffered.

The corrected music was then sent to Ludwig Erk and inscribed in the King’s book, and in every Christmas book in the world since then, as: “Silent Night,” “by Mohr and Gruber.”