In his book, Return to Order, author John Horvat described a spirit of unrestraint that dominated culture and economy, which he called frenetic intemperance. The following article is part of a series of articles on American intemperance in the twentieth century written by history teacher Edwin Benson that explains some stages by which America adopted this spirit of frenetic intemperance and its consequence in society. This article illustrates how the Great Depression contributed to the advancement of the restless spirit of frenetic intemperance, and especially to the increase in power of the executive branch of the federal government.

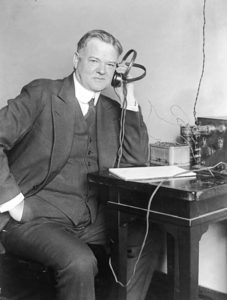

As the thirties dawned, it became obvious that Herbert Hoover’s optimistic words, “we shall soon, with the help of God, be within sight of the day when poverty shall be banished from this nation,”[1] were hopelessly optimistic.

Herbert Hoover’s reputation as a hidebound conservative is highly ironic. That reputation was largely crafted by Franklin D. Roosevelt and his followers to make Hoover a punching bag to build support for the far-reaching laws that will be discussed later. As Hoover’s actions are reanalyzed by historians less spellbound by Roosevelt’s oratory, it is becoming increasingly more obvious that Hoover was in fact more a Progressive in the mold of Woodrow Wilson than a Calvin Coolidge conservative.[2]

Hoover had been a poor orphan—his parents both died before he was eight—who made a fortune as a mining engineer. When World War I broke out, Hoover— then 39—left his engineering practice to run an organization funneling food into Belgium. When the United States entered the war, President Wilson made Hoover the head of the U.S. Food Administration. In both roles, Hoover’s reputation soared. Trumpeting Hoover’s rags-to-riches story, he was referred to in the press as “the great humanitarian” and “the great engineer.”

His fame and the fact that he had been nominally Republican before the war, enabled Hoover to remain in government after the Republican Warren Harding won the election of 1921. Harding named him Secretary of Commerce, a post that he continued to hold under Calvin Coolidge after Harding’s death. Hoover was an activist in the otherwise more restrained Coolidge Administration. Coolidge himself is supposed to have referred to Hoover derisively as “wonder boy”.

Hoover’s prediction about the end of poverty was not mere political ballyhoo, but was based on a thoroughly developed political philosophy. That philosophy was actually based on “Enlightenment” ideas. He was something of an heir of the English philosopher Adam Smith. To put it simply, Hoover saw economics as a scientific process, which he and other great minds had mastered. By applying that process, prosperity could be guaranteed in perpetuity. On the surface, he was a proponent of laissez faire, the idea that government’s role in the economy was to leave it alone and let the economy work. In practice, Hoover was more than willing to use government regulation to make sure it worked properly.

Hoover’s superficial reputation as a conservative became popular as Franklin Roosevelt, aided by Hoover’s own lack of ability in public relations, cast the great engineer as the demon of the Depression.

It was under the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt that the root of frenetic intemperance—planted by his distant cousin Theodore and tended by Wilson and Hoover—really bloomed under the guise of the New Deal. All restraint to executive action was thrown off. Every Progressive idea that was not passed before World War I was dusted off and rushed into law. Roosevelt’s “Brain Trust”—a group of liberal scholars drawn primarily from Harvard and Columbia universities—proposed sweeping new ideas of their own. These were rushed into law by a Congress that could hardly wait to do FDR’s bidding.

[like url=https://www.facebook.com/ReturnToOrder.org]

Historians, both those sympathetic and critical of Roosevelt, see him as an experimenter who was willing to try any idea that promised to help end the Great Depression. Philosophy and ideology yielded to expediency in the Roosevelt Administration. The one strain that unites the New Deal was an increase in power of the executive branch of the federal government.

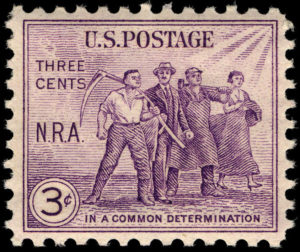

An attempt to list the entire raft of New Deal programs would be far outside the scope of this article. Partial lists can be found in any good American history textbook. However, the all-inclusive spirit of the time can be seen by examining the capstone of Roosevelt’s first “Hundred Days” in office—the National Recovery Administration (NRA).

The NRA attempted to draft “codes of fair competition” for every industry in the country. What the drafters of those codes meant by fair competition was actually the establishment of highly regulated cartels. In this new order, government would control all industrial behavior. This would include production, distribution, pricing, and—especially—the relationship between employers and employees. Labor unions, a very important constituency for Roosevelt, were imposed on all industries. Wages and working conditions became integral parts of the codes because a long-cherished idea of many progressives was that “cut-throat competition” was one factor that drove wages down. A regulated marketplace would be the harbinger of prosperity for all.

The second head of the NRA, Donald Richberg summed up the attitude, “Unless industry is sufficiently socialized by its private owners and managers so that great essential industries are operated under public obligation appropriate to the public interest in them, the advance of political control over private industry is inevitable.”[3]

Left unsaid was the fact that Richberg’s ultimatum really left no choice at all except whether socialism would be voluntary or mandatory.

So far-reaching was the NRA that the Supreme Court unanimously found it to be unconstitutional when a New York chicken butcher illegally allowed a customer to choose the chickens he wished to buy instead of following the random process that the code demanded.

So far-reaching was the NRA that the Supreme Court unanimously found it to be unconstitutional when a New York chicken butcher illegally allowed a customer to choose the chickens he wished to buy instead of following the random process that the code demanded.

The administration responded by demanding “reform” of the Supreme Court and by having its allies in Congress draft new laws that separated and then passed new laws embodying important parts of the NRA. Among these laws was “Labor’s Magna Carta,” the Wagner Act. Many of these new laws were allowed by the Court in part because several of its members died or resigned and were replaced by Roosevelt appointees. Eventually, Roosevelt appointed eight justices during his twelve years in the White House. Two of those justices would still be on the court twenty-five years after Roosevelt’s death.

It was Roosevelt’s fate to be president during the two great crises of the early twentieth century—the Great Depression and World War II. Both gave him ample opportunity to recast the government in his own progressive image and advance the restless spirit of frenetic intemperance that overthrew traditional restraints.

________________________________

[1] Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover accepting the Republican nomination for the presidency, August 11, 1928.

[2] Perhaps the most popular scholarly reappraisal of the Great Depression is to be found in the works of Amity Schlaes, Coolidge and The Forgotten Man. Insights into the relationship of Hoover and Wilson can be gained by reading the article “Herbert Hoover Describes the Ordeal of Woodrow Wilson”, published in American Heritage Magazine in June 1958. It is available on the internet at http://www.americanheritage.com/content/herbert-hoover-describes-ordeal-woodrow-wilson.

[3] Quoted in Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. The Coming of the New Deal [Vol. II of The Age of Roosevelt], First Mariner Books Edition, (Boston – New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003), p. 115.