One of the delights of going to Holy Mass in a place which one has never before visited is the discovery of the church building itself.

There is an inexpressible joy in walking into a traditionally decorated Catholic church for the first time. The Gothic architecture draws the eye heavenward. The stained glass fills the nave with a kind of unpredictable yet reassuring light. The colors are vivid and varied. The symbols of the faith are all about you. There are the heroes of the faith as the best artists in that area depicted them in glass, stone, wood, paint, and mosaic. The whole gives a marvelous sense of the richness of the faith. It is both obvious and mysterious. The images are larger than life, but at the same time one wonders exactly which saints are being shown, what the symbols mean, and why the people who sacrificed to build this building chose those particular saints and symbols.

If you are fortunate and have the time to explore the building, you can often get some ideas about the people themselves. Small brass plates, panes of glass at the bottom of the windows, stones carved with names. Certain nationalities often predominate—Irish, German, Polish, Italian, etc. It is not hard to imagine them huddled on the deck of a steamer landing in New York City like the photos seen in a documentary. “How,” you might think, “did those poorly clad people ever manage to build anything so magnificent?”

If you are even more fortunate, a member of the parish might notice you and come over to guide you about. You might hear stories about a group of bricklayers or fresco painters who worked ten hours a day and then came to the building site to donate their labor into the early hours of the morning. You might hear of the successful immigrant businessman so bereft at the loss of the wife who helped him become successful that he donated the Saint Cecilia window in the choir loft with her name on it.

Unfortunately, there is also the contrary experience—where you walk into a fine old church building and everything is beige, the altar is little more than a table, and you don’t know in which direction to genuflect because you can’t find the tabernacle.

What Does Saint Thomas Say About Immigration?

In downtown Louisville, Kentucky stands the Cathedral of the Assumption. It is a fine red-brick building, finished in 1852. As you climb the too-many steps to get into the main body of the cathedral, it is easy to wonder what architectural delights may lay behind those large doors. A wonderfully friendly person hands you the bulletin. You walk in. This being a Gothic building you look up to see a marvelous star-studded sea of blue between the intricate vaults. Then you look down and all your reveries end. You are confronted with the baptistery. It is marble and it is big. It has a little Gothic detail, but it is too low, out of scale, somehow just wrong. The altar is marble, too, and had some Gothic elements, but you have to get a lot closer before you can see them. The wall behind the altar looks like it was lifted from a modern cemetery chapel with large unbroken slabs of marble. The chairs look like something ordered in bulk from an eighties office supply company. You just know that something else had to be here once upon a time.

Sure enough, there was. This being the Age of the Internet, a page devoted to the history of the cathedral is online.1 Most of the pictures are modern, but there is one rather grainy picture postcard from the early twentieth century showing it as it used to be.

How could this vandalism have taken place? Maybe there was a horrible fire that destroyed that part of the building. Was there a flood that heavily damaged all of that irreplaceable decoration?

How could this vandalism have taken place? Maybe there was a horrible fire that destroyed that part of the building. Was there a flood that heavily damaged all of that irreplaceable decoration?

What does Saint Thomas Aquinas say about Marriage?

No, this was not an act of God, it was an act of man—people who just could not understand the richness around them. At this point, I will step aside and let Steve Kaufman, a journalist for Louisville Insider take over:

One tangible result of Vatican II, visible to all Louisvillians — and especially its Catholics — was a new look for the churches themselves.

Communion rails, those barriers separating priest and congregation, were mostly removed so the worshipers could feel more involved. The high, formidable altars were lowered to make the priest feel more accessible and reoriented toward the congregation. The tabernacle was moved to the side. And the seating plan was changed from rigid and rectilinear to a less formal, more social circular or semicircular arrangement.

“The call was for ‘full and active participation,’” says Sr. Jean Zappa, chapel preservation specialist for the Ursuline Sisters of Louisville. “And the modern architecture was more about being warm and welcoming, versus the enormity of space that makes those feel smaller in the presence of God.”

The exterior architecture of the churches changed as well. Solid stone fortresses with rigid classical forms and steeples reaching to the sky became, more and more, “yesterday’s churches.” More modern buildings with flat or rounded roofs and angled walls began to proliferate.2

[like url=https://www.facebook.com/ReturnToOrder.org]

Yes, who can deny the “warm and welcoming” quality of slabs of marble or the flat walls of unadorned brick that typify so many churches built since the sixties. Lest this sound too dismissive, there is beauty to be found in Louisville’s cathedral—it is just that everything that is beautiful is also old.

A far more uplifting experience was Asheville, North Carolina’s Basilica of Saint Lawrence. The exterior is something that is difficult to imagine coming out of the Smokey Mountains. According to the basilica’s brochure, the architectural style is Spanish Renaissance. The exterior is full of detail and variation. Statues stand at the roofline, almost as sentries at watch on some medieval castle. These are the soldiers of God’s army, stationed to keep the enemy at bay.

A far more uplifting experience was Asheville, North Carolina’s Basilica of Saint Lawrence. The exterior is something that is difficult to imagine coming out of the Smokey Mountains. According to the basilica’s brochure, the architectural style is Spanish Renaissance. The exterior is full of detail and variation. Statues stand at the roofline, almost as sentries at watch on some medieval castle. These are the soldiers of God’s army, stationed to keep the enemy at bay.

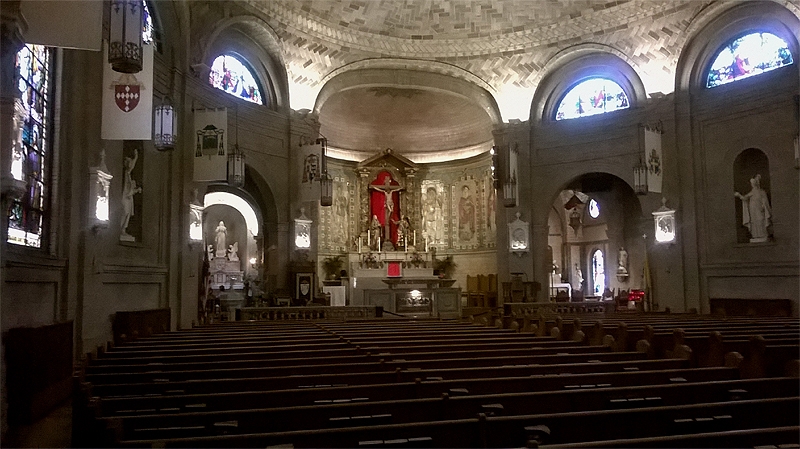

The real delight, though, comes when you enter. It is cool and a little dark. The actual entrance is small, but then you turn a little bit and walk a couple steps and you are greeted with the magnificence of the worship space. The whole space is one large oval dome set in tile. There is marvelous stained glass. There are statues half-hidden in niches that you can’t really see until you are standing right in front of them

As you walk in, your eye is drawn to the main altar surmounted by a life-size crucifix. Our Lady and Saint John, the beloved disciple, looking on in a mixture of love and horror. Around Our Lord are mosaics representing the company of saints.

As you walk in, your eye is drawn to the main altar surmounted by a life-size crucifix. Our Lady and Saint John, the beloved disciple, looking on in a mixture of love and horror. Around Our Lord are mosaics representing the company of saints.

On the right and left of the altar are two side chapels. The one to the left contains a beautifully carved baptismal font. The baptisms that take place there are intimate, family occasions with the Blessed Mother of us all and her angel attendants looking on.

On the right and left of the altar are two side chapels. The one to the left contains a beautifully carved baptismal font. The baptisms that take place there are intimate, family occasions with the Blessed Mother of us all and her angel attendants looking on.

Why We Need Beauty in Our Lives

Why We Need Beauty in Our Lives

On the right side of the altar is the Blessed Sacrament Chapel, equally beautiful—a fitting place for Our Lord to repose as the faithful come to adore Him.

Some modern voices might cry out, “How can you justify all of this opulence when the hungry are all around us?”

The answer is as simple as it is profound. We are all hungry, and it is a hunger of the soul. We are hungry for the true, the good, and the beautiful. Praise God for those who designed, built, and preserve those beautiful places in which our souls can be fed!

1. https://wikivisually.com/wiki/Cathedral_of_the_Assumption_(Louisville%2C_Kentucky)

2. Steve Kaufman, “Steve Wiser to chronicle the evolving history of Catholic church architecture in Louisville,” Insider Louisville, September 20, 2017, retrieved Aug. 6, 2018 at https://insiderlouisville.com/lifestyle_culture/steve-wiser-to-chronicle-the-evolving-history-of-catholic-church-architecture-in-louisville/