In his book, Return to Order, author John Horvat described a spirit of unrestraint that dominated culture and economy, which he called frenetic intemperance. The following article is part of a series of articles written by history teacher Edwin Benson that explains some stages by which America adopted this spirit of frenetic intemperance and its consequence in society. This article shows how two very different intemperate viewpoints led nevertheless to the same outcome during the fifties, and the effects it had on the children of this era.

The fifties actually lasted longer than a decade. What Americans think of as “the fifties” started with victory in World War II and ended with the Kennedy Assassination and large scale involvement in Vietnam.

Two world views vied for dominance during the fifties, both intemperate in very different ways. The first, very cautious in outlook, was expressed by those who had been permanently scarred by the Great Depression. The other was held by the economic optimists.

Those whose psyches were dominated by the horrors of the Great Depression worried about their security for the rest of their lives. Fearful of change, they tended to cling to their jobs. They also tended to live well within their means. They never took the risk of borrowing money that they might not be able to repay. They would appear to be unlikely to contribute to an intemperate society. However, that assumption would be incorrect. First, their actions and thoughts were often ruled by an inordinate concern about money. Second, they favored keeping the New Deal programs that they credited with ending the Depression. This encouraged continuing high government spending and taxation.

The second brand of frenetic intemperance involved the optimism of the fifties. This outlook became so popular that it is a point of nostalgia for many Americans and recalled in films and television shows. In some respects, this brand closely resembled that of the twenties. In both periods, credit-fueled spending helped the standard of living to increase significantly.

There were, however, many differences.

Perhaps the most important of those differences was the baby boom. The prosperity of the twenties saw the birth rate decrease, while the period from 1946-1964 occasioned two decades of high fertility and birthrates.

During the twenties, many were attracted to the high salaries and bright lights of the big cities, whereas the baby boom encouraged movement away from the cities. By the fifties, many wanted the economic advantages of the city while raising their children in fresh air and sunshine outside of town. After the war, this lifestyle was available to almost anyone with a steady income.

Accelerating this trend was the Veteran’s Administration (VA) mortgage. World War II veterans, a group that comprised of over fifteen million Americans in 1950, could purchase a home with no down payment. However, that home had to be in an area that the VA considered a safe investment. Their definition left out most older homes in urban areas, but new houses in the suburbs were very welcome indeed.

This move to the suburbs spawned other major changes. Families needed two cars so that Dad could drive one to work while Mom did the shopping and ran the children back and forth to school and other activities. It appeared to make little sense to put old furniture and appliances into a new house. Unlike the impromptu athletic contests of the city streets and playgrounds, suburban children needed uniforms and the correct equipment. Often, these items were purchased on credit. The stores that provided them moved out of town, too.

[like url=https://www.facebook.com/ReturnToOrder.org]

Perhaps, though, the biggest harbinger of frenetic intemperance was the introduction of television. In it, advertisers discovered a highly successful selling machine. It brought dozens of hours of constantly changing passive entertainment—as well as hundreds of sixty-second commercials—directly into the home every day. Politics and current events could be observed from the comfort of the sofa. Family-based situation comedies like Father Knows Best, Leave it to Beaver, Ozzie and Harriet, and many others presented the prosperous life as the only normal and ideal way to live. The radio of the twenties never could be as effective as the hypnotizing light in the corner of the living room.

Another expensive element entered the lives of most Americans—the vacation. The idea that the American worker deserved a couple weeks off each year became all but universal. Many chose to build a smaller and more rustic version of suburbia in a forest or next to a lake. Others hit the road in search of new sights, spending the night at Holiday Inns or Howard Johnson’s. Those of more limited means bought camping equipment to “rough it” in a rapidly expanding network of state parks within a few minutes of the new interstate highways.

Connected with all of this spending was the concept often expressed as “keeping up with the Joneses.” There was massive pressure to live up to the expectations of one’s neighbors and colleagues. Not purchasing the latest stove, refrigerator or washing machine was a sign that a man did not care much about his wife. To drive a car that was more than five years old was tantamount to an admission that one could not feed one’s children. Children without enough spending money risked rejection by their peers.

The fifties saw an explosion of what came to be called the youth culture. In fact, it can be argued that the period saw the birth of the teenager—a group who had some of the economic power of adults without the responsibilities that traditionally went along with it. In 1944, about 43% of 17-18-year-olds graduated from high school. By 1948 that number was 54%, increasing to 62% in 1956 and 76% by 1964.[1] If one factors in the increasing numbers going to college, it becomes obvious that many American young adults could delay entering the workforce for years. The teens were seen as a time of carefree fun (funded by Dad), rather than the beginning of adult responsibility.

This trend was also pushed by many parents who had suffered through the Great Depression and resolved to give their children advantages that they had been denied. This attitude created a group with money to spend, but no responsibility to earn it. Sellers, especially in music, fashion, and the movies, leapt to scoop up the dollars that teenagers were spreading around.

This trend was also pushed by many parents who had suffered through the Great Depression and resolved to give their children advantages that they had been denied. This attitude created a group with money to spend, but no responsibility to earn it. Sellers, especially in music, fashion, and the movies, leapt to scoop up the dollars that teenagers were spreading around.

All of these elements, and several others, contributed to a common obsession about money and the things that money could buy. The drive to raise one’s standard of living required advancement at work, and careerism became almost an article of faith in “the American way of life.”

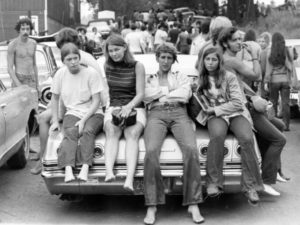

Curiously, it was many of those same children of the fifties that would spend the late sixties as foot soldiers in a highly intemperate rebellion against the prosperity that their parents had labored so hard to provide.

________________________________

[1] Kenneth A. Simon and W. Vance Grant, U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Digest of Educational Statistics, 1969 Edition, (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1969) p. 47, Table 64. Available online at http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED035996.pdf.