In his book, Return to Order, author John Horvat described a spirit of unrestraint that dominated culture and economy, which he called frenetic intemperance. The following article is part of a series of articles written by history teacher Edwin Benson that explains some stages by which America adopted this spirit of frenetic intemperance and its consequence in society. His first article deals with the Progressive Era at the beginning of the twentieth century and focuses on how government became intemperate.

If one had to put a date on the birth of frenetic intemperance in the United States government, that date would likely be September 14, 1901. On that dark day, William McKinley, twenty-fifth President of the United States, succumbed to the after-effects of a pair of assassin’s bullets.

Much more than an amiable and courtly man passed from the scene that day. With McKinley passed the structure of government as envisioned by the founding fathers and described in the Constitution.

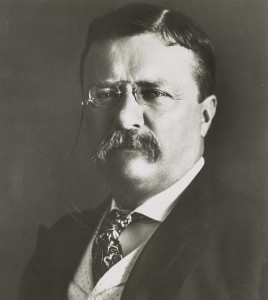

At 2:15 that morning, Theodore Roosevelt became president.

Even at the distance of over a century, it is difficult to dislike Theodore Roosevelt. Scholar, naturalist, rancher, author, explorer, athlete, historian, statesman, and an involved father of six beautiful children—Roosevelt was a truly impressive man. With all his attainments, he took a childlike delight in life’s adventures. British diplomat and long-time friend, Cecil Spring-Rice famously said, “You must always remember that the president is about six.”[1]

Around Roosevelt formed the first American cult of personality since that of George Washington. That cult of personality made it possible for Roosevelt to accumulate power that went far beyond traditional Constitutional restraints.

[like url=https://www.facebook.com/ReturnToOrder.org]

Of course, Roosevelt could not have done it all by himself, no matter how gifted he was. The atmosphere was ready for him. Citizens in many walks of life resisted the increasing power of gigantic corporations. Workers, farmers, cities, and many state legislatures were (or at least believed themselves to be) under the control of “captains of industry” who became fabulously wealthy.[2]

A new political ideology, called Progressivism, taught that only the national government had the power to put limits on the “malefactors of great wealth,” as well as corrupt political machines. Progressives especially targeted railroads and banks, often arguing that the national government should heavily regulate—if not actually own—those industries. The idea that took hold was that a giant could only be controlled by an even bigger giant.

Just as they do today, “Progressives” had allies in the press. A new type of journalist, dubbed muckrakers, specialized in seeking out and publicizing abuses in business and corruption in big city governments. By using highly descriptive prose, they were able to attract the interest of the general public to issues that had always been decided behind closed doors—or ignored altogether.

An important example concerned the meatpacking industry. In a traditional world, those who did not raise their own meat purchased it from local butchers who had in turn purchased the animals from local farmers. It was possible for the consumer to actually know the farmer who raised and the butcher who processed the steak on his dinner table. Meatpacking was one of the first businesses to be industrialized. Within a few years, that same consumer would eat meat that was raised near Dallas, sold in Abilene, and processed in Chicago, even if he lived in Buffalo.

The traditional system was highly regulated, even though the government had nothing to do with it. A farmer who sold a diseased cow to the butcher would never be trusted again. A butcher who sold his customer rancid meat would soon find himself without customers. It was a simple idea, regulate yourself or go out of business.

Under the new system, there was little effective regulation. The owner of a huge meatpacking house barely knew his employees, much less the suppliers or consumers. If a sick cow got into the pens, the packing house had a significant incentive to pass it on to a consumer who would probably never know the difference—and would not be missed by the company if he did. It was a situation tailor-made for abuse.

Enter the muckraker Upton Sinclair. Wanting to write about the plight of industrial workers, his book, The Jungle, horrified readers with graphic descriptions of the way the ham on their table got there. Famously, Sinclair quipped, “I aimed at the public’s heart, and by accident I hit it in the stomach.”

A horrified public turned to Roosevelt, who was only too happy to expand government power into this most intimate part of the American home. To meet public demand, Roosevelt played a major role in passing the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. These laws, in turn, became the nucleus of the Food and Drug Administration.

This was not Roosevelt’s only victory. Railroad freight rates, the wages of coal miners, the number of competitors in the steel industry, and many others felt the new weight of federal government regulation. In a frenetic burst of energy, Roosevelt’s Department of the Interior took over control of 230 million acres of land, mostly in the west.[3] The adverse effect on landowners and on those who legally used those acres went unnoticed.

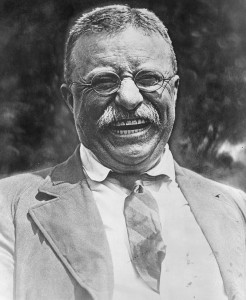

Those who denounced Roosevelt’s extra-constitutional actions were likely to be seen as the stooges of big business. The general public found these issues far less interesting than Roosevelt’s latest hunting trip, frolics with his children, or plunge in the Navy’s experimental submarine. To many, “Teddy” was the government, and they liked and trusted him.

Finally, the calendar ran out on Roosevelt. On March 4, 1909, he turned over power to a new president. The new man, William Howard Taft, had been handpicked by Roosevelt. All the public did was to ratify Roosevelt’s choice. No president since Andrew Jackson had been so popular at the end of his presidency as to be able to do that.

Taft was no Roosevelt, but there are historians who argue that Taft actually accomplished more “Progressive” action than Roosevelt did.

Eventually, Roosevelt turned on Taft, citing his supposed abandonment of “Progressive” values. Roosevelt wanted to be in control of the presidency again, and the facts didn’t matter. When Taft didn’t retreat, the two of them split the Republican Party. This cleared the way for the election of the Democrat, Woodrow Wilson.

Wilson, with the look and speech of the cool academic that he was, didn’t have Roosevelt’s hold on the affections of the public, either. It didn’t matter. After Roosevelt, personality was no longer necessary to move the country in a “Progressive” direction. Roosevelt helped the nation buy into the basic idea that frenetic government action was more trustworthy than frenetic big business. Ignored was the fact that the frenetic intemperance of big government could also come to control small business, small towns, and individuals.

Wilson, with the look and speech of the cool academic that he was, didn’t have Roosevelt’s hold on the affections of the public, either. It didn’t matter. After Roosevelt, personality was no longer necessary to move the country in a “Progressive” direction. Roosevelt helped the nation buy into the basic idea that frenetic government action was more trustworthy than frenetic big business. Ignored was the fact that the frenetic intemperance of big government could also come to control small business, small towns, and individuals.

It was a mistake that the public would make again—over and over again—for the rest of the century. Later incarnations of the “Progressives” are still making it, and are trying to force the public to make it, too.

________________________________

[1] Edmond Morris, The Rise of Theodore Roosevelt (New York, Random House, 1979), page xxii.

[2] See Chapter 4 of Return to Order for a more complete discussion of the effects of gigantism in business.

[3] Almanac of Theodore Roosevelt at http://www.theodore-roosevelt.com/trenv.html.